4. The Object-Oriented Programming Paradigm

In this chapter, we recap the object-oriented programming paradigm with examples in Scala. As discussed, we take object-oriented code to mean code that includes definitions of domain models, i.e., basic domain- or application-specific abstractions, or uses object-oriented frameworks (as opposed to general-purpose object-oriented libraries).

4.1. Making command-line applications testable

Marking the beginning of our transition to the object-oriented paradigm, we had to define a new abstractions (type)

to make the sliding queue application testable.

In particular, we defined an Observer for decoupling the applications “business logic” from the decition whether to print recurring updates to the console (for production use) or to store them in a data structure (for testing).

interface OutputObserver extends Predicate<Queue<String>> {}

A predicate (in Java) is an object with a single test method that takes one argument and returns a boolean result:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Predicate<T> {

boolean test(T t);

}

The only reason to use this instead of not returning anything (return type void) is to give the caller access to possible I/O errors, upon which we might want to exit the application.

public void process(final Stream<String> input, final OutputObserver output) {

input

.takeWhile(

word -> {

queue.add(word); // the oldest item automatically gets evicted

return output.test(queue);

})

.count(); // forces evaluation of the entire stream

}

By having factored the application’s main logic out to a method with input and output arguments, we can now invoke this logic in two different scenarios:

For production use as a main program, we pass a stream representing stdin and an observer instance whose test method brings back the original behavior of printing the argument.

final OutputObserver outputToConsole = value -> { System.out.println(value); // terminate on I/O error such as SIGPIPE return !System.out.checkError(); };

For testing, we pass a stream representing our hardcoded test data and an observer instance whose test method stores the argument in a data structure, which we can inspect to verify the correct sequence of output values.

private static class OutputToList implements OutputObserver { final List<Queue<String>> result = new ArrayList<>(); @Override public boolean test(final Queue<String> value) { final var snapshot = new LinkedList<>(value); result.add(snapshot); return true; } }

A typical test would then look like this:

public void testSlidingWindowNonempty() { final var sut = new SlidingQueue(3); final var input = Stream.of("asdf", "qwer", "oiui", "zxcv"); final var outputToList = new OutputToList(); sut.process(input, outputToList); final var result = outputToList.result; assertEquals(4, result.size()); assertEquals(List.of("asdf"), result.get(0)); assertEquals(List.of("asdf", "qwer"), result.get(1)); assertEquals(List.of("asdf", "qwer", "oiui"), result.get(2)); assertEquals(List.of("qwer", "oiui", "zxcv"), result.get(3)); }

Let’s take a moment to reflect by comparing the original straight-line, scripting-style version of the sliding queue application with this version. The original version was not as testable because of the interweaving of I/O with the application’s logical functionality. The current version meets our functional requirements, i.e., behaves in the same interactive way as the original version, but additionally meets our nonfunctional testability and scalability requirements. This sounds great, but where is the catch?

Basically, the price of reconciling these forces pulling us in different directions is a significantly more complex design involving custom object-oriented abstractions, such as the OutputObserver.

The endpoint of this journey thereby marks our transition to the object-oriented paradigm.

Note

The test shown above only checks whether the total output is correct after processing the entire input given. So we still have to test the correct interactive behavior of our sliding queue logic, i.e., every time we consume an input value, we produce an output showing the updated queue. The console app and iterators examples illustrate how to set up a mini-framework for testing the interactive correctness of our code.

4.2. Defining domain models in object-oriented languages

In this section, we’ll discuss how to use object-oriented language constructs to define a domain model, i.e., a set of domain-specific building blocks for our application, in contrast with general-purpose library classes.

In typical imperative languages, the basic type abstractions are

Addressing: pointers, references

Aggregation: structs/records, arrays

Example: a node in a (singly) linked list, consisting of a value and a successor.

(Structural) recursion: defining a type in terms of itself, usually involves aggregation to be useful

Example: a node in a linked list, whose successor is also a node in a linked list.

In typical object-oriented languages, the additional basic type abstractions are

Variation: tagged unions, multiple implementations of an interface

Example: mutable set abstraction

add element

remove element

check whether an element is present

check if empty

how many elements

There are several possible implementations:

reasonable: binary search tree, hash table, bit vector (for small underlying domains)

less reasonable: array, linked list

see also this table of collection implementations

Genericity (type parameterization): when a type is parametric in terms of one or more type parameters

Example: collections parametric in their element type.

These abstractions are often combined, e.g., aggregation, structural recursion, and genericity all together when defining a tree interface with implementation classes for leaves and interior nodes, where the data values have the same arbitrary type.

enum Tree[A] deriving CanEqual:

case Leaf[A](val data: A) extends Tree[A]

case Node[A](val children: Tree[A]*) extends Tree[A]

scala> import Tree.*

scala> Node(Node(Leaf(3), Leaf(4)), Leaf(5))

val res0: Tree[Int] = Node(ArraySeq(Node(ArraySeq(Leaf(3), Leaf(4))), Leaf(5)))

In an object-oriented language, we commonly use a combination of design patterns (based on these basic abstractions) to represent domain model structures and associated behaviors:

4.3. Object-oriented Scala as a “better Java”

Scala offers various improvements over Java, including:

traits: generalization of interfaces and restricted form of abstract classes, can be combined/stacked

package structure decoupled from folder hierarchy

null safety: ensuring at compile-time that an expression cannot be null

multiversal equality: making sure apples are compared only with other apples

higher-kinded types (advanced topic)

Todo

More recent versions of Java, however, have started to echo some these advances:

lambda expressions

default methods in interfaces

local type inference

streams

records

We will study these features as we encounter them.

The following examples illustrate the use of Scala as a “better Java” and the transition to some of the above-mentioned improvements:

4.4. Modularity and dependency injection

Object-oriented language constructs can also help us organize the higher-level structure of our code to make the code “better” with respect to certain design principles and code quality requirements.

Note

To wrap your head around this section, you may want to start by recalling/reviewing the stopwatch example from COMP 313/413 (intermediate object-oriented programming). In that app, the model is rather complex and has three or four components that depend on each other. After creating the instances of those components, you had to connect them to each other using setters. Does that ring a bell? In this section and the pertinent examples, we are achieving basically the same goal by plugging two or more Scala traits together declaratively.

4.4.1. Design goals

We pursue following design goals tied to the nonfunctional code quality requirements:

testability

modularity for separation of concerns

reusability for avoidance of code duplication (“DRY”)

In particular, to manage the growing complexity of a system, we usually try to decompose it into its design dimensions, e.g.,

mixing and matching interfaces with multiple implementations

running code in production versus testing

We can recognize these in many common situations, including the examples listed below.

In object-oriented languages, we often use classes (and interfaces) as the main mechanism for achieving these design goals.

4.4.2. Scala traits

Scala traits are abstract types that can serve as fully abstract interfaces as well as partially implemented, composable building blocks (mixins). Unlike Java interfaces (prior to Java 8), Scala traits can have method implementations (and state). The Thin Cake idiom shows how traits can help us achieve our design goals.

Note

We deliberately call Thin Cake an idiom as opposed to a pattern because it is language-specific.

We will rely on the following examples for this section:

First, to achieve testability, we can define the desired functionality, such as common.IO, as its own trait instead of a concrete class or part of some other trait such as common.Main.

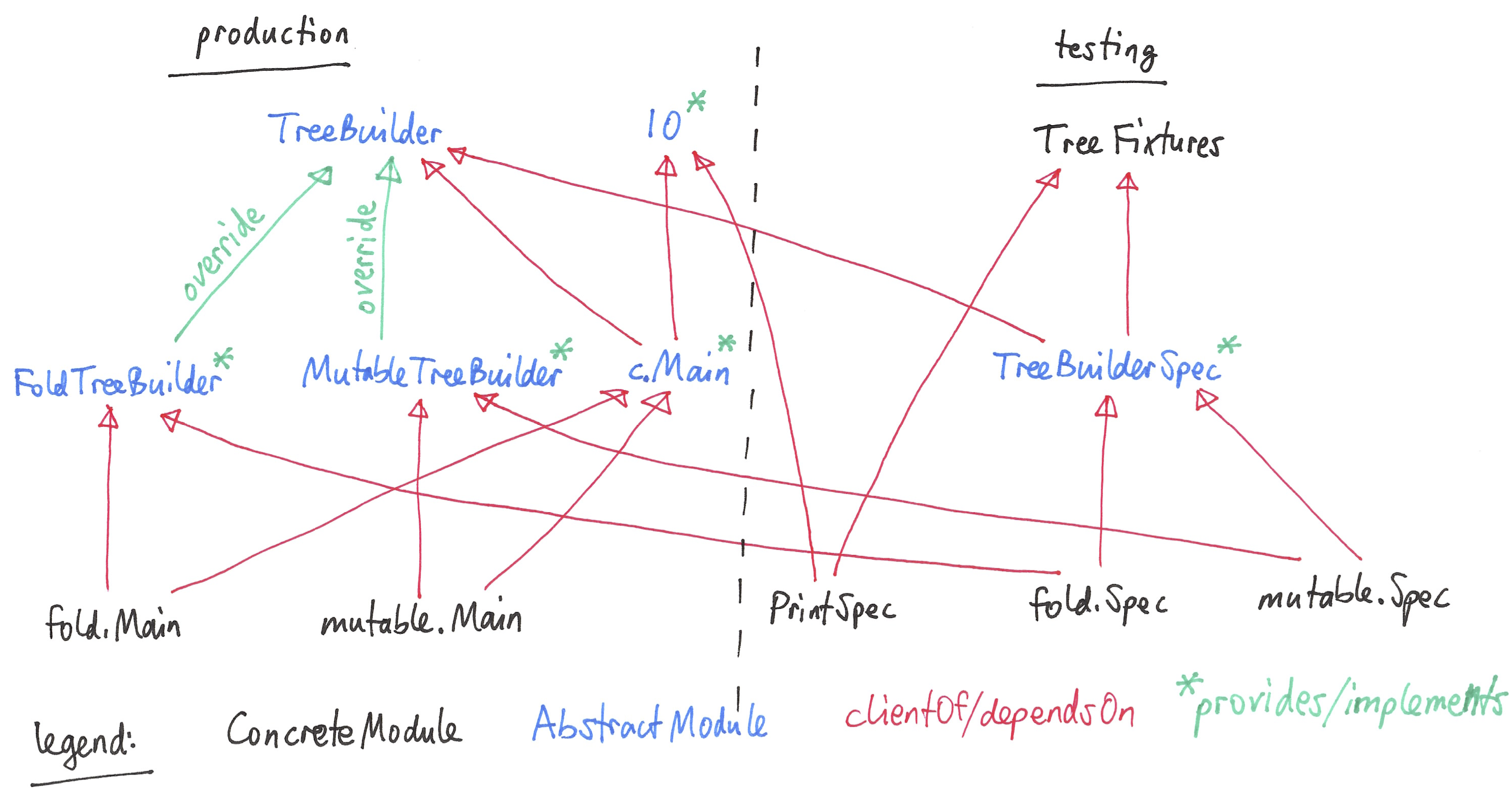

Such traits are providers of some functionality, while building blocks that use this functionality are clients, such as``common.Main`` (on the production side) and PrintSpec (on the testing side).

Specifically, in the process tree example, we use PrintSpec to test common.IO in isolation, independently of common.Main.

To avoid code duplication in the presence of the design dimensions mentioned above, we can again leverage Scala traits as building blocks. Along some of the dimensions, there are three possible roles:

provider, e.g., the specific implementations MutableTreeBuilder, FoldTreeBuilder, etc.

client, e.g., the various main objects on the production side, and the TreeBuilderSpec on the testing side

contract, the common abstraction between provider and client, e.g., TreeBuilder

Usually, when there is a common contract, a provider overrides some or all of the abstract behaviors declared in the contract.

Some building blocks have more than one role. E.g., common.Main is a client of (depends on) TreeBuilder but provides the main application behavior that the concrete main objects need.

Similarly, TreeBuilderSpec also depends on TreeBuilder but provides the test code that the concrete test classes (Spec) need.

This arrangement enables us to mix-and-match the desired TreeBuilder implementation with either common.Main for production or TreeBuilderSpec for testing.

The following figure shows the roles of and relationships among the various building blocks of the process tree example.

The imperative versions of the iterators example includes additional instances of trait-based modularity in its imperative/modular package.

By contrast, the functional versions of this example rely on parameterized types (generics) to achieve a similar outcome.

Note

For pedagogical reasons, the process tree and iterators examples are overengineered relative to their simple functionality: To increase confidence in the functional correctness of our code, we should test it; this requires testability, which drives the modularity we are seeing in these examples. In other words, the resulting design complexity is the cost of testability. On the other hand, a more realistic system would likely already have substantial design complexity in its core functionality for separation of concerns, maintainability, and other nonfunctional quality reasons; in this case, the additional complexity introduced to achieve testability would be comparatively small.

4.4.3. Trait-based dependency injection

In the presence of modularity, dependency injection (DI) is a technique for supplying a dependency to a client from outside, thereby relieving the client from the responsibility of “finding” its dependency, i.e., performing dependency lookup. In response to the popularity of dependency injection, numerous DI frameworks, such as Spring and Guice, have arisen.

The Thin Cake idiom provides basic DI in Scala without the need for a DI framework.

To recap, common.Main cannot run on its own but declares by extending TreeBuilder that it requires an implementation of the buildTree method.

One of the TreeBuilder implementation traits, such as FoldTreeBuilder can satisfy this dependency.

The actual “injection” takes place when we inject, say, FoldTreeBuilder into common.Main in the definition of the concrete main object fold.Main.